I have been a long time estranged from posting in this blog. And in parallel, I have a long time felt estranged in my relationship with my Father. That is to say, not only have I not been to church for several weeks, but I have not taken the time to pray, to read, to serve, to worship, to the point of relative estrangement.

I know that I have often said, because it is true, that you don't need to perform any purifying rites or jump through hoops or meet prerequisites to draw close to God. You don't need to become clean, pure, and good in order to approach Jesus because the point is Jesus's redemptive grace, not the worthiness of our offerings. So is it right that I feel estranged from God when I haven't been paid attention to Him in a while? It's not as if I have to wash myself in some river or sacrifice a spotless lamb or subsidize an orphanage in Darfur, and then I can go to church on a buzz of righteousness. In a very syllogistic sense, sin means separation from God, Jesus's death saves us from our sin, therefore our estrangement from God is stripped away wholly by Jesus's sacrifice. But in a relational sense, if you've wandered away from your lover for a while, there's a very personal process of reconciliation that needs to be worked through by both parties.

I'm reminded by the culmination of the story of the prodigal son in Luke 15. Surely, the son knew that his father was good and merciful. But after squandering his wealth in wild living and falling to the abject position of feeding pigs for a living, the son returned home with humility, yes, and meekness, yes, but also a sense of estrangement. The son said to himself, I will go back to my father and say to him: Father, I have sinned against heaven and against you. I am no longer worthy to be called your son; make me like one of your hired men.

The son returns with no sense of entitlement. He knows who his father is. But does he see himself as a beloved heir because of his father's extravagant love? Or does he see himself as a son estranged from his father, beginning the road to restitution? Dramatic irony prevails; we know how the story ends. The prodigal son is embraced joyously by his father, who sets aside his judgment, wrath, and sorrow, and runs to welcome his lost child home. And in a certain sense, I guess it's less important to figure out whether the prodigal son was right or wrong to feel such abject undeserving because this story is a true and human story, and whether or not we should feel that way, when I have estranged myself from God, I do feel like the prodigal son and I do feel that God runs to me with welcoming and encircling arms.

I used to identify more with the older brother: the one who was patient and diligent for years and never got the recognition he deserved. I used to be troubled by that the idea that I was siding with the wrong perspective, and thought it would be a sign of wisdom and a realization of truth when I finally came around to identifying with the younger brother, the prodigal son.

I prefer suspended chords to tonal resolution in music, but I think I prefer reconciliations to estrangements in real life.

Sunday, August 1, 2010

Wednesday, May 26, 2010

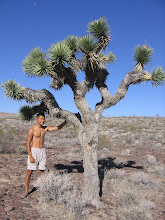

Hot Sun, Dry Sand, Empty Nalgenes

I've liked deserts for a few years now. I originally liked mountains exclusively, and I still like mountains, but as someone once said, there's always gonna be another mountain. Deserts convey this wonderful sense of expanse and vastness, this sense that you're seeing all there is to see and at the same time, there's more beyond the horizon in every direction; and they test the adventurer's mettle in a different way than a mountain. Where a mountain will dictate how quickly or deliberately you climb, what vistas will unfold around the next switchback, or the level of your adrenaline as you navigate a particular sector, a desert makes the challenge simple and puts it directly in your control: how far are you willing to go?

Usually, when I venture into the desert, I bring a finite number of Nalgene bottles with me, and when I run out of water, I turn back. (I hate it when authors casually reference their experience like that, as if most authors have ever spent a lot of time climbing Mount McKinley or rebuilding a war-torn African village, but know that I have been in a lot of deserts.) This method pretty much tells me how far I can allow myself to go with a guaranteed assurance of survival.

Several thousand years ago, a group of liberated Hebrew slaves also set out in a jaunty exodus into the desert of Sinai, and they also carried a finite amount of water in urns or sheepskins or whatever sufficed before BPA-free polypropylene came into common usage. They probably refilled all their containers on the eastern side of the Red Sea, knowing it might be some time before they had another opportunity, and headed off following a giant pillar of cloud or fire, depending on outdoor lighting. And at a certain point, they ran out of water.

To this point, the Children of Israel and I share a relatively common experience. Faith is the point at which you shake your water bottles empty and continue into the desert based only on the promises of God's deliverance.

At a certain point when I was living in Charleston, I remember thinking it funny that I had recently purchased three used books, and all three of them had to do with the main characters crossing desert landscapes, and two of them were about them perishing in the wild. The defining characteristic of a desert is that there's no obvious water out there, so it's not the same as rolling the dice and committing yourself to fate. Once you've run out of the water you brought, your plan is pretty much no plan. So it took a lot of faith on the part of the Children to continue on to what most of us would call probable death. Especially since, as some pointed out, they could've just returned to Goshen. But the Children carried on into the wilderness for forty long years, relying on God alone, unable to use anything they had brought to ensure their survival. This allegory is true in terms of our ultimate condition of sin and our need to be saved by God, but physically, corporeally, I don't think I've ever been in such a place of trust, in a place where I so exclusively needed God's provision.

The Children did not always acquit themselves with grace and patient faith. They complained bitterly, rebelled, and doubted the Lord, wrongfully. But they were in a place in the desert, astoundingly dependent on God's provision, that few of us have seen. Few of us have the faith to shake our water bottles empty and continue our journey reliant on the providence of God.

Usually, when I venture into the desert, I bring a finite number of Nalgene bottles with me, and when I run out of water, I turn back. (I hate it when authors casually reference their experience like that, as if most authors have ever spent a lot of time climbing Mount McKinley or rebuilding a war-torn African village, but know that I have been in a lot of deserts.) This method pretty much tells me how far I can allow myself to go with a guaranteed assurance of survival.

Several thousand years ago, a group of liberated Hebrew slaves also set out in a jaunty exodus into the desert of Sinai, and they also carried a finite amount of water in urns or sheepskins or whatever sufficed before BPA-free polypropylene came into common usage. They probably refilled all their containers on the eastern side of the Red Sea, knowing it might be some time before they had another opportunity, and headed off following a giant pillar of cloud or fire, depending on outdoor lighting. And at a certain point, they ran out of water.

To this point, the Children of Israel and I share a relatively common experience. Faith is the point at which you shake your water bottles empty and continue into the desert based only on the promises of God's deliverance.

At a certain point when I was living in Charleston, I remember thinking it funny that I had recently purchased three used books, and all three of them had to do with the main characters crossing desert landscapes, and two of them were about them perishing in the wild. The defining characteristic of a desert is that there's no obvious water out there, so it's not the same as rolling the dice and committing yourself to fate. Once you've run out of the water you brought, your plan is pretty much no plan. So it took a lot of faith on the part of the Children to continue on to what most of us would call probable death. Especially since, as some pointed out, they could've just returned to Goshen. But the Children carried on into the wilderness for forty long years, relying on God alone, unable to use anything they had brought to ensure their survival. This allegory is true in terms of our ultimate condition of sin and our need to be saved by God, but physically, corporeally, I don't think I've ever been in such a place of trust, in a place where I so exclusively needed God's provision.

The Children did not always acquit themselves with grace and patient faith. They complained bitterly, rebelled, and doubted the Lord, wrongfully. But they were in a place in the desert, astoundingly dependent on God's provision, that few of us have seen. Few of us have the faith to shake our water bottles empty and continue our journey reliant on the providence of God.

Tuesday, May 11, 2010

To the Unknown God

Back in college, when I was going through a stagnant period in my relationship with God, my college ministry advisor suggested that I re-read the stories of Biblical role models. Abraham, Moses, David, the Apostles. Jesus. I think oftentimes when we think of analyzing a role model, we start out with the blanket approach of finding application and "we should do as they do," so when we read that Stephen admonished the Pharisees, we instantly begin to think of modern-day Pharisees that we're supposed to be admonishing. And sometimes we skip that step of actually considering what these Biblical heroes did and appreciating in humility how greatly they acted for God.

Incidentally, South Park just put out an episode entitled "The Tale of Scrotie McBoogerballs" that cautions the viewer not to enter a reading of a text with too many preconceptions. Well, that was one of the lessons, among many, from that episode.

In my eyes, Acts 17 is one of those episodes for Paul that stands out as a high point in his ministry simply by the feat alone, not because it was Paul and we're supposed to be like Paul. The act is a speech Paul gives. The place is Areopagus. The audience is a group of Athenian philosophers who "spent their time doing nothing but talking about and listening to the latest ideas."

Paul begins his speech acknowledging that the Athenians are very religious. He mentions that he has carefully studied their objects of worship and found an altar labeled TO THE UNKNOWN GOD: a philosophical ideation of the unknownable. He then boldly posits that he is going to reveal this unknown god to them. Paul then describes in short the nature of our monotheistic creator God, emphasizing the difference between an omnipotent spiritual God and a human-formed idol and explaining the relationship we are meant to have with this God. He incorporates a quotation from a Greek poet and uses it as the basis for further thought. He ends his speech with the admonition that in the past, God overlooked idolatry, but those days are over and judgment is pending through a man that God demonstrably raised from the dead.

Let's look at what Paul did there, in just a few paragraphs. Sometimes we read too much into the written text of an oratory, forgetting that speeches are meant to be heard in the moment and not re-analyzed on a line by line basis, but the Athenians are erudite enough to indulge us on this one.

Paul demonstrates that he is familiar with the Athenian religious and philosophical beliefs. He has made a careful study of their temples and their idols, he knows of their religious devotion, and he even quotes one of their poets' writing to them. How many Christians out there take such a righteous pride in their oblivion to other cultures, including pop culture? I certainly haven't studied the holy texts or practices of other religions enough to engage them on their own terms. I couldn't quote you one passage from the Koran or the Bhagavad Gita. But Paul wouldn't have been effective here if he had just sailed in the breezeway of the temple and started selling his own wares without any appreciation for the mindset of the people he was supposed to be engaging.

Yet even as Paul acknowledges the Athenians' piety and philosophy, he is bold enough still to declare the truth of God in no uncertain terms. He says, "You say there is an unknown God. Here is the God you do not know." It is a remarkable segue, both unashamed and sensitive. Paul realizes that these men are searching for truth: it is a mark of wisdom to acknowledge that there are things we do not and cannot know. Instead of rebuking them for their polygamy and idolatry, he recognizes that they are searching and points the way to the truth. Paul also doesn't hold back on his authority on the truth. Sometimes, we get herded too far down the path of acknowledging the unknown. We might desire too much to find common ground, and when someone says, "Well, can we really know anything about God and Jesus?" we might hesitate to declare an absolute truth, and instead fall back to a subjective "Well, we can't know anything for certain sure, here's what has worked in my life." The truth is that we can't know everything; the truth is also that there are some things we do know, things that we have considered carefully and found to be true and corroborated by the Holy Spirit, and we should share those things unashamedly. And somehow, delicately and confidently, Paul threads the needle between sensitivity and audacity in this section of his speech. It's a trick we would do well to learn.

It's worth noting that Paul does not launch into an exposition on the life and sacrificial death of Jesus in this speech. If you're reading the passage for an instant apply-to-my-life, you might find this absence problematic because how are you supposed to present the gospel without the four-step methodology? But if you're reading the passage and appreciating that it's Paul talking to a group of intellectuals and doing so brilliantly, it's more than an example. It's upper level oratory. But it is an interesting question and maybe an inexplicable gap, considering that the Athenians began the exchange by asking Paul to explain his new teaching on Jesus and His resurrection. Paul only mentions those items at the conclusion of his speech, as demonstration of God's intent for man to repent. One has to wonder how much the Athenians have already heard about the gospel of Jesus.

The speech ends with the reception given it by the Athenians in the crowd. Some sneered, some said that they wanted to hear more thoughts on the matter, and some became disciples. Sometimes we can hear truth and only sometimes it will move us.

Incidentally, South Park just put out an episode entitled "The Tale of Scrotie McBoogerballs" that cautions the viewer not to enter a reading of a text with too many preconceptions. Well, that was one of the lessons, among many, from that episode.

In my eyes, Acts 17 is one of those episodes for Paul that stands out as a high point in his ministry simply by the feat alone, not because it was Paul and we're supposed to be like Paul. The act is a speech Paul gives. The place is Areopagus. The audience is a group of Athenian philosophers who "spent their time doing nothing but talking about and listening to the latest ideas."

Paul begins his speech acknowledging that the Athenians are very religious. He mentions that he has carefully studied their objects of worship and found an altar labeled TO THE UNKNOWN GOD: a philosophical ideation of the unknownable. He then boldly posits that he is going to reveal this unknown god to them. Paul then describes in short the nature of our monotheistic creator God, emphasizing the difference between an omnipotent spiritual God and a human-formed idol and explaining the relationship we are meant to have with this God. He incorporates a quotation from a Greek poet and uses it as the basis for further thought. He ends his speech with the admonition that in the past, God overlooked idolatry, but those days are over and judgment is pending through a man that God demonstrably raised from the dead.

Let's look at what Paul did there, in just a few paragraphs. Sometimes we read too much into the written text of an oratory, forgetting that speeches are meant to be heard in the moment and not re-analyzed on a line by line basis, but the Athenians are erudite enough to indulge us on this one.

Paul demonstrates that he is familiar with the Athenian religious and philosophical beliefs. He has made a careful study of their temples and their idols, he knows of their religious devotion, and he even quotes one of their poets' writing to them. How many Christians out there take such a righteous pride in their oblivion to other cultures, including pop culture? I certainly haven't studied the holy texts or practices of other religions enough to engage them on their own terms. I couldn't quote you one passage from the Koran or the Bhagavad Gita. But Paul wouldn't have been effective here if he had just sailed in the breezeway of the temple and started selling his own wares without any appreciation for the mindset of the people he was supposed to be engaging.

Yet even as Paul acknowledges the Athenians' piety and philosophy, he is bold enough still to declare the truth of God in no uncertain terms. He says, "You say there is an unknown God. Here is the God you do not know." It is a remarkable segue, both unashamed and sensitive. Paul realizes that these men are searching for truth: it is a mark of wisdom to acknowledge that there are things we do not and cannot know. Instead of rebuking them for their polygamy and idolatry, he recognizes that they are searching and points the way to the truth. Paul also doesn't hold back on his authority on the truth. Sometimes, we get herded too far down the path of acknowledging the unknown. We might desire too much to find common ground, and when someone says, "Well, can we really know anything about God and Jesus?" we might hesitate to declare an absolute truth, and instead fall back to a subjective "Well, we can't know anything for certain sure, here's what has worked in my life." The truth is that we can't know everything; the truth is also that there are some things we do know, things that we have considered carefully and found to be true and corroborated by the Holy Spirit, and we should share those things unashamedly. And somehow, delicately and confidently, Paul threads the needle between sensitivity and audacity in this section of his speech. It's a trick we would do well to learn.

It's worth noting that Paul does not launch into an exposition on the life and sacrificial death of Jesus in this speech. If you're reading the passage for an instant apply-to-my-life, you might find this absence problematic because how are you supposed to present the gospel without the four-step methodology? But if you're reading the passage and appreciating that it's Paul talking to a group of intellectuals and doing so brilliantly, it's more than an example. It's upper level oratory. But it is an interesting question and maybe an inexplicable gap, considering that the Athenians began the exchange by asking Paul to explain his new teaching on Jesus and His resurrection. Paul only mentions those items at the conclusion of his speech, as demonstration of God's intent for man to repent. One has to wonder how much the Athenians have already heard about the gospel of Jesus.

The speech ends with the reception given it by the Athenians in the crowd. Some sneered, some said that they wanted to hear more thoughts on the matter, and some became disciples. Sometimes we can hear truth and only sometimes it will move us.

Saturday, February 20, 2010

Romans vs James

When posed with the query, "I really have intentions to start reading the Bible again. Where is a good book to start?" I would always point to Romans. Romans is a great summation of Christian theology, written in very organized and accessible language, and its chapters flow from one logical thesis to the next. The first chapter describes humanity's moral corruption and deviation from God, the second continues on to explain the law that delineates between holy and unholy and the condemnation under which we stand, and the rest of the book goes through the arguments of whether Jewishness is of spiritual import, the exemplification of godly faith by Abraham the patriarch, the explication of God's provision and our redemption through Jesus Christ, the exhortation to live transformed and righteous lives as new believers, our obligation and indebtedness to God's divine law, the explanation of the great hope we have in God's salvation, and the call to bring the gospel to the Jews and to the nations. In fact, most evangelical Christian literature follows a similar model: describe God's perfection and creationist relationship with man, demonstrate man's sin and corruption, show Jesus as the hope and assurance of salvation, and give counsel to lead transformed and missional lives in response to the gospel truth. Romans is overall an excellent read for establishing the basics about sin, the law, salvation, grace, and the relationship between God, Jesus, me, and you.

For the advanced subscriber to the gospel of Christ, I've recently decided to point to the book of James. Once upon a time, I was pretty dismissive of James because here was my understanding of the epistle:

Chapter 1, be persevering under trials, check.

Chapter 2, faith without works is dead, understood.

Chapter 3, no man can tame the tongue, simple concept.

Chapter 4, be nice and humble and peacemakers, okay.

Chapter 5, be patient for the Lord's coming and pray a lot, got it.

It's not that I oversimplified the text, although that certainly is true of most of my literary distillations. James is not a difficult or abstruse read. It lacks the bizarre prophecies, scriptural cross-references, or theological nuances that are more replete in a lot of other New Testament books. James is, to the casual reader, an easy book.

But the more I've progressed in my pursuit of Christ, the more I am convinced that this Christian life and our approach to scripture is not based in conceptual understanding. It is a benchmark of maturity for Christians that they progress from being able to read and interpret the Bible on an intellectual level to becoming the people that exemplify the better parts of God-inspired character. The first time you read James 1, you might read it like I read Proverbs: good wisdom, good advice for living so that we can all play nicely with each other. But the next time you read James 1, maybe you'll consider Jesus dying so that we could shrug off the shackles of sin, the dregs of our very nature, and become one with God and become like Him in righteousness, and you'll be humbled by the sort of person you are supposed to be: a person who welcomes trials and difficulties with joy in his heart, a person who takes pride in his humble circumstances knowing that he is where God wants him, a person who perseveres patiently through harsh circumstance spurred onward by an eternal perspective, a person who is quick to listen, slow to speak, and slow to anger, a person who keeps a tight rein on his tongue, a person who looks out for widows and orphans and keeps himself pure. And that's only the first chapter, succeeded by the chapter that tells you that faith without substantiating works is in vain.

If you read that passage not with the goal of conceptual understanding, (check, I've got this passage down) but with perspective on the sort of person you are and the sort of Christ-like nature God expects of His servants, it is utterly humbling and transforming, and you come to an awestruck understanding that only through God's grace and the transforming work of the Holy Spirit will you become anything like that because it's not in our nature. You come to appreciate that Jesus modeled this righteousness to unfettered perfection. You draw closer to God's heart.

Romans is a good book for the head. James is a good book for the heart. As Peekay would say, first with the head, and then with the heart. Ecclesiastes is probably Level III.

For the advanced subscriber to the gospel of Christ, I've recently decided to point to the book of James. Once upon a time, I was pretty dismissive of James because here was my understanding of the epistle:

Chapter 1, be persevering under trials, check.

Chapter 2, faith without works is dead, understood.

Chapter 3, no man can tame the tongue, simple concept.

Chapter 4, be nice and humble and peacemakers, okay.

Chapter 5, be patient for the Lord's coming and pray a lot, got it.

It's not that I oversimplified the text, although that certainly is true of most of my literary distillations. James is not a difficult or abstruse read. It lacks the bizarre prophecies, scriptural cross-references, or theological nuances that are more replete in a lot of other New Testament books. James is, to the casual reader, an easy book.

But the more I've progressed in my pursuit of Christ, the more I am convinced that this Christian life and our approach to scripture is not based in conceptual understanding. It is a benchmark of maturity for Christians that they progress from being able to read and interpret the Bible on an intellectual level to becoming the people that exemplify the better parts of God-inspired character. The first time you read James 1, you might read it like I read Proverbs: good wisdom, good advice for living so that we can all play nicely with each other. But the next time you read James 1, maybe you'll consider Jesus dying so that we could shrug off the shackles of sin, the dregs of our very nature, and become one with God and become like Him in righteousness, and you'll be humbled by the sort of person you are supposed to be: a person who welcomes trials and difficulties with joy in his heart, a person who takes pride in his humble circumstances knowing that he is where God wants him, a person who perseveres patiently through harsh circumstance spurred onward by an eternal perspective, a person who is quick to listen, slow to speak, and slow to anger, a person who keeps a tight rein on his tongue, a person who looks out for widows and orphans and keeps himself pure. And that's only the first chapter, succeeded by the chapter that tells you that faith without substantiating works is in vain.

If you read that passage not with the goal of conceptual understanding, (check, I've got this passage down) but with perspective on the sort of person you are and the sort of Christ-like nature God expects of His servants, it is utterly humbling and transforming, and you come to an awestruck understanding that only through God's grace and the transforming work of the Holy Spirit will you become anything like that because it's not in our nature. You come to appreciate that Jesus modeled this righteousness to unfettered perfection. You draw closer to God's heart.

Romans is a good book for the head. James is a good book for the heart. As Peekay would say, first with the head, and then with the heart. Ecclesiastes is probably Level III.

Tuesday, February 9, 2010

Ghost of Christmas Recent

23 December.

Here are my notes from the Christmas service I put together for interested crew members:

It’s easy to see, in a theological sense, why Good Friday and Easter are important commemorations for Christians. Jesus’s sacrificial death and subsequent supernatural resurrection are the cornerstone of our salvation and our restitution with God our Father. But why is Christmas, the supposed celebration of Christ’s birth, important to the believing Christian?

A possible and increasingly common answer is that it’s not. Many people would point to the season’s commercialist nature, the date December 25th’s origin in the pagan festival of Saturnalia, and the seeming insignificance of a birthday as a divine milestone to infer that the observance of Christmas is irrelevant to the Christian faith.

In response, I came up with two serious reasons that Christmas might be a worthwhile occasion to celebrate. The first stems from the precedent that it is appropriate to celebrate special days to commemorate special occurrences. In the book of Leviticus, God ordained the Feast of Passover for the Israelites to remember their deliverance, the Feast of Unleavened Bread to further remember His distinctions of holy and unholy provision, and the Feast of Tabernacles to remember their time of nomadic itinerance and utter dependence on God in the wilderness. Although not biblically mandated, it seems also appropriate to celebrate a special day commemorating Jesus’s arrival into the world: the miraculous beginning to a very special and remarkable 33 years, perhaps the greatest 33 years in the history of mankind. Even if it’s since been moved to the wrong day, it’s a day worth celebrating.

The second argument for Christmas is the significance of Jesus’s incarnation. It’s true that His death on the cross was what saved us from sin, overcame death, and captured eternal life for believers. But His life among us on earth gives an inexorable, indelible portrait of the sort of God we’re supposed to worship: it’s a historically true rendering of a God who really loves us. If you feel sorry for someone, you give them a handout. We observe this behavior in the way we give to the Salvation Army or the Vietnam Vet around Christmastime. We feel sorry for the disenfranchised and the destitute, we see that it is right to help, and we give. But if you love someone, you leave where you are and go to them. If your brother or sister had fallen into difficult times, you would buy a plane ticket and travel thousands of miles to be with them. And given our plight and sinful condition, our God responded not with some blanket, impersonal measure, but instead left where He was and came to us Himself.

I like to think, and I think it’s reasonable to think, that Jesus didn’t see His time on earth solely as an obligation towards the plan of salvation, but that He actually likes us and liked to spend time with us. He wept with Martha and Mary, ate with His disciples, took the time to coach and mentor them personally, played with little children. His coming to earth was a matter of love, not duty. And Christmas is a celebration of, yes, His coming to earth in human form.

It is an important truth that God loved us not only enough to die for us, a one-time event, but enough to live with us day in and day out and still love us. In light of that love so demonstrated, how then should I live?

2 February.

My most recent favorite passage: James 1:26-27:

“If anyone considers himself religious and yet does not keep a tight rein on his tongue, he deceives himself and his religion is worthless. Religion that God our Father accepts as pure and faultless is this: to look after orphans and widows in their distress and to keep oneself from being polluted by the world.”

Here are my notes from the Christmas service I put together for interested crew members:

It’s easy to see, in a theological sense, why Good Friday and Easter are important commemorations for Christians. Jesus’s sacrificial death and subsequent supernatural resurrection are the cornerstone of our salvation and our restitution with God our Father. But why is Christmas, the supposed celebration of Christ’s birth, important to the believing Christian?

A possible and increasingly common answer is that it’s not. Many people would point to the season’s commercialist nature, the date December 25th’s origin in the pagan festival of Saturnalia, and the seeming insignificance of a birthday as a divine milestone to infer that the observance of Christmas is irrelevant to the Christian faith.

In response, I came up with two serious reasons that Christmas might be a worthwhile occasion to celebrate. The first stems from the precedent that it is appropriate to celebrate special days to commemorate special occurrences. In the book of Leviticus, God ordained the Feast of Passover for the Israelites to remember their deliverance, the Feast of Unleavened Bread to further remember His distinctions of holy and unholy provision, and the Feast of Tabernacles to remember their time of nomadic itinerance and utter dependence on God in the wilderness. Although not biblically mandated, it seems also appropriate to celebrate a special day commemorating Jesus’s arrival into the world: the miraculous beginning to a very special and remarkable 33 years, perhaps the greatest 33 years in the history of mankind. Even if it’s since been moved to the wrong day, it’s a day worth celebrating.

The second argument for Christmas is the significance of Jesus’s incarnation. It’s true that His death on the cross was what saved us from sin, overcame death, and captured eternal life for believers. But His life among us on earth gives an inexorable, indelible portrait of the sort of God we’re supposed to worship: it’s a historically true rendering of a God who really loves us. If you feel sorry for someone, you give them a handout. We observe this behavior in the way we give to the Salvation Army or the Vietnam Vet around Christmastime. We feel sorry for the disenfranchised and the destitute, we see that it is right to help, and we give. But if you love someone, you leave where you are and go to them. If your brother or sister had fallen into difficult times, you would buy a plane ticket and travel thousands of miles to be with them. And given our plight and sinful condition, our God responded not with some blanket, impersonal measure, but instead left where He was and came to us Himself.

I like to think, and I think it’s reasonable to think, that Jesus didn’t see His time on earth solely as an obligation towards the plan of salvation, but that He actually likes us and liked to spend time with us. He wept with Martha and Mary, ate with His disciples, took the time to coach and mentor them personally, played with little children. His coming to earth was a matter of love, not duty. And Christmas is a celebration of, yes, His coming to earth in human form.

It is an important truth that God loved us not only enough to die for us, a one-time event, but enough to live with us day in and day out and still love us. In light of that love so demonstrated, how then should I live?

2 February.

My most recent favorite passage: James 1:26-27:

“If anyone considers himself religious and yet does not keep a tight rein on his tongue, he deceives himself and his religion is worthless. Religion that God our Father accepts as pure and faultless is this: to look after orphans and widows in their distress and to keep oneself from being polluted by the world.”

Friday, January 1, 2010

I'm On A Boat

I remember in Rosencrantz and Guildenstern Are Dead, there was a great metaphor using a boat in the middle of an open ocean as a commentary on existentialist direction, or lack thereof. And in Searching for God Knows What, Don Miller explains how humans view and interact with each other in terms of a lifeboat metaphor. It's my turn to explain what the spiritual implications are of being on a boat.

I'll start with some observations on not-being-on-a-boat, since that's probably a common experience for most prospective readers. If you're not on a boat, and you're trying to live a gospel-centered life, you could easily find yourself with a lot of decisions to make. Whether to go to this church or that one. Whether to actually go to this church or that one. Whether to hang out with this set of Christian friends, or this set of non-Christian friends. Whether to spend time in the homeless ministry or mentoring the youth group. Whether to spend discipleship time reading a book, working in a soup kitchen, or just forgoing the practice altogether. Whether to tithe and how much. The simple and powerful decision to follow Christ can somehow manifest itself in a lot of pick-and-choose as to what features you want to upgrade your package of Christian lifestyle.

When you're on a boat, you're confined to a 300 foot cylinder several hundred feet underwater with 150 other guys in a complicated and demanding work environment. The paradigm of decision-making is distilled to one decision: every day, all you can decide, and all you have to decide, is whether to follow Jesus or not.

You have no privacy. Your life is utterly transparent because you live, eat, sleep, and work in the same 300 foot cylinder. This transparency precludes the duplicity of any sort of double lifestyle that self-conscious Christians sometimes find themselves in: party hard on Saturday night, then show up at church the next morning and smile at everybody; or be angry at your wife and children and then show up to the office with a genial temperament. If you're having a bad day, you can't decide to stay at home until you can make yourself presentable to the outside world. If you have a secret addiction to pornography, you can't shut the door so no one will know. You are who you are.

The sentiment of "you are who you are" is troubling for people who don't like who they are or who feel that they're not who they should be. But the truth is we should be very pleased with who we are because we are supposed to be redeemed by the salvation of Christ, made new in His image, transformed through the continual work of the Holy Spirit. We are to have been perfected. So this test of transparency, of being on a boat, is a test of whether you really believe that you stand where you say you do with Jesus. If you believe in the transforming grace of the gospel, then the fact that you are who you are is not a source of shame but a glorious testimony to the gospel of Christ.

Being on a boat also means that you have nonstop opportunities to live out the gospel because you can't defer the nonstop instances of interaction with other people. The questions of how to forgive, how to show mercy, how to turn the other cheek, and how to be a servant are much less academic because you are afforded those chances all day, every day. And you can't choose your church, and you can't choose whether you're surrounded by people you like or not: you've got what you're given. So it's not ever a question of whom you're going to love, but whether or not you're going to love. If you think about that condition, it's a truer sort of love.

Many people do not have the chance to be on a boat in the same way that I am on a boat. But I think it's still a good idea every once in a while to distill all decisions away from decisions regarding circumstance and focus on whether we want to follow Christ or not.

I'll start with some observations on not-being-on-a-boat, since that's probably a common experience for most prospective readers. If you're not on a boat, and you're trying to live a gospel-centered life, you could easily find yourself with a lot of decisions to make. Whether to go to this church or that one. Whether to actually go to this church or that one. Whether to hang out with this set of Christian friends, or this set of non-Christian friends. Whether to spend time in the homeless ministry or mentoring the youth group. Whether to spend discipleship time reading a book, working in a soup kitchen, or just forgoing the practice altogether. Whether to tithe and how much. The simple and powerful decision to follow Christ can somehow manifest itself in a lot of pick-and-choose as to what features you want to upgrade your package of Christian lifestyle.

When you're on a boat, you're confined to a 300 foot cylinder several hundred feet underwater with 150 other guys in a complicated and demanding work environment. The paradigm of decision-making is distilled to one decision: every day, all you can decide, and all you have to decide, is whether to follow Jesus or not.

You have no privacy. Your life is utterly transparent because you live, eat, sleep, and work in the same 300 foot cylinder. This transparency precludes the duplicity of any sort of double lifestyle that self-conscious Christians sometimes find themselves in: party hard on Saturday night, then show up at church the next morning and smile at everybody; or be angry at your wife and children and then show up to the office with a genial temperament. If you're having a bad day, you can't decide to stay at home until you can make yourself presentable to the outside world. If you have a secret addiction to pornography, you can't shut the door so no one will know. You are who you are.

The sentiment of "you are who you are" is troubling for people who don't like who they are or who feel that they're not who they should be. But the truth is we should be very pleased with who we are because we are supposed to be redeemed by the salvation of Christ, made new in His image, transformed through the continual work of the Holy Spirit. We are to have been perfected. So this test of transparency, of being on a boat, is a test of whether you really believe that you stand where you say you do with Jesus. If you believe in the transforming grace of the gospel, then the fact that you are who you are is not a source of shame but a glorious testimony to the gospel of Christ.

Being on a boat also means that you have nonstop opportunities to live out the gospel because you can't defer the nonstop instances of interaction with other people. The questions of how to forgive, how to show mercy, how to turn the other cheek, and how to be a servant are much less academic because you are afforded those chances all day, every day. And you can't choose your church, and you can't choose whether you're surrounded by people you like or not: you've got what you're given. So it's not ever a question of whom you're going to love, but whether or not you're going to love. If you think about that condition, it's a truer sort of love.

Many people do not have the chance to be on a boat in the same way that I am on a boat. But I think it's still a good idea every once in a while to distill all decisions away from decisions regarding circumstance and focus on whether we want to follow Christ or not.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)